Salvador Dali: The Accommodations of Desire

The Spanish-born artist Salvador Dalí was officially allied with Surrealism from 1929 to 1941, and even afterward his work continued to reflect the influence of Surrealist thought and methodology. His flamboyance, flair for drama and self-promotion, and hyperactive imagination reinvigorated the movement and its public popularity. Dalí, who was given to hallucinations and paranoiac visions, cultivated these outrageous subjects for his paintings, rendering them so meticulously that they were unsettling in their clinical matter-of-factness. Such pictures exemplified the Surrealist preoccupation with dreams and the unconscious.

Painted in the summer of 1929, “The Accommodations of Desire” is a small gem that deals with Dalí’s sexual anxieties over a love affair with an older, married woman. The woman, Gala, then the wife of the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, became Dalí’s life-long muse and mate. In this picture, which Dalí painted after taking a walk alone with Gala, he included seven enlarged pebbles on which he envisioned what lay ahead for him: “terrorizing” lions’ heads (not so “accommodating” to his “desires” as the title of the painting facetiously suggests), as well as a toupee and a colony of ants (a symbol of decay). Also depicted are various vessels (one in the shape of a woman’s head) and three figures embracing on a platform. Dalí did not paint the lion heads but, rather, cut them out from what must have been an illustrated children’s book, slyly matching the latter’s detailed style with his own. These collaged elements are virtually indistinguishable from the super-saturated color and painstaking realism of the rest of the composition, startling the viewer into questioning the existence of the phenomena recorded and of the representation as a whole.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 907, 1st floor

Salvador Dali: Crucifixion

Dalí utilized his theory of “nuclear mysticism,” a fusion of Catholicism, mathematics, and science, to create this unusual interpretation of Christ’s crucifixion. Levitating before a hypercube—a geometric, multidimensional form—Christ’s body is healthy, athletic, and bears no signs of torture; the crown of thorns and nails are missing. The artist’s wife, Gala, poses as a devotional figure, witnessing Christ’s spiritual triumph over corporeal harm. Several dreamlike elements from Dali’s earlier Surrealist work feature in this painting: a levitating figure, vast barren landscape, and chessboard.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 913, 1 st floor

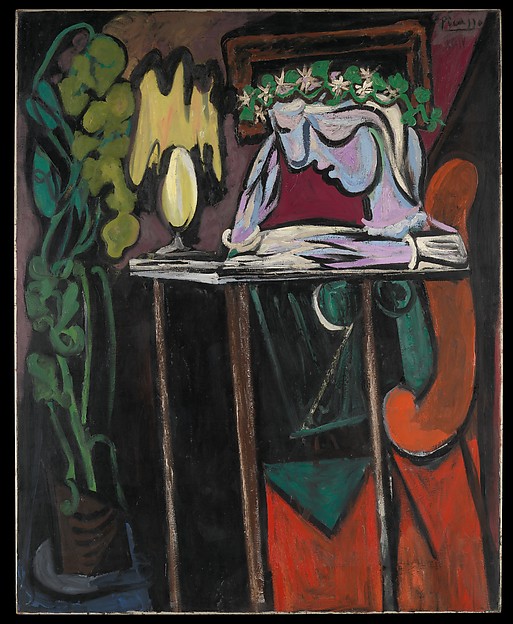

Pablo Picasso: Reading at a Table

In this painting of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter reading a book, Picasso returns to a favored subject: a woman seated alone. The darkened room and glow from the lamp give her an ethereal presence, while her alabaster skin, blonde hair, and floral crown enhance her youth. Though she featured prominently in Picasso’s work at the time, their relationship was the least public of Picasso’s many amatory alliances, a fact that imbues this painting with a sense of tender intimacy. The canvas, one of several similar compositions Picasso painted of his mistress, is a poem by a man in love.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 901, 1st floor

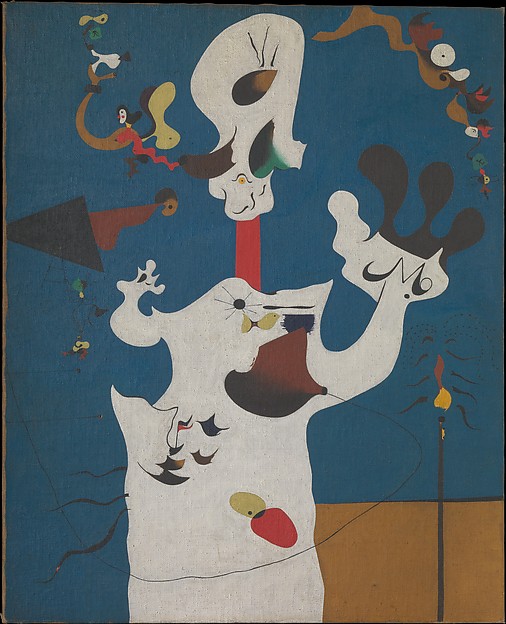

Joan Miro: Potato

Born in the Spanish province of Catalonia, Joan Miró was deeply influenced by his country’s native landscape and artistic heritage. Although he was associated with French Surrealism and its practitioners and lived in Paris during the early part of his career, he returned to settle in Spain after World War II. This deliberate remove from the center of the art world is symptomatic of Miró’s independence, a temperament that would mark his art as well as his life. Drawing on the possiblilities of free invention encouraged by Surrealism, Miró developed a style that drew from highly personalized and psychological references. Often beginning with a recognizable starting point, Miró transformed his subjects through whimsical color and free play with form.

“The Potato” is emblematic of Miró’s poetic riffs on reality. It takes as its subject a gigantic female figure who stretches her arms wide. She is set against a blue sky and above a patch of earth—perhaps a potato field. The billowing white shape of the figure is attached to a red post in the center of the composition like a scarecrow on a pole. Miró surrounded his merry “potato-earth-woman” with fanciful decorative objects, some of which are “earthy” and some not. The figure has one brown-and-black breast that “squirts” a long, black, winding thread, as elfin creatures flutter in the sky around her. At the left, a red and yellow “butterfly-woman” takes flight from her brown banana-like nose as other creatures climb a ladder—one of Miró’s favorite motifs. Beyond the earthiness of the subject, the painting’s title appears to be derived from the representation of an actual, recognizable potato: lodged in the woman’s forehead is a small, brown, oval object with three tendrils growing out of its upper edge.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 906, 1st floor

Vasily Kandinsky: Improvisation 27

In his influential treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky theorized a new form of artistic expression that would reject the materialist world in favor of emotional and spiritual ideals, using abstract forms and color symbolism to evoke an inner, preconscious world. Composed of dark lines and abstract colorful masses, Improvisation 27 depicts three iterations of an embracing couple surrounded by serpentine forms. Kandinsky hints at the painting’s possible subject in the subtitle “Garden of Love II,” likely a reference to biblical Eden.

Signatures, Inscriptions, and Markings

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 910, 1st floor

Edgar Degas: The Dance Class

This work and its variant in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, represent the most ambitious paintings Degas devoted to the theme of the dance. Some twenty-four women, ballerinas and their mothers, wait while a dancer executes an “attitude” for her examination. Jules Perrot, a famous ballet master, conducts the class. The imaginary scene is set in a rehearsal room in the old Paris Opéra, which had recently burned to the ground. On the wall beside the mirror, a poster for Rossini’s Guillaume Tell pays tribute to the singer Jean-Baptiste Faure, who commissioned the picture and lent it to the 1876 Impressionist exhibition.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 815, 2nd floor

葛饰北斋:神奈川沖浪裏

Not on view. Hei-hei.

Anselm Kiefer: Winter Landscape

Not on view.

Vincent van Gogh: Wheat Filed with Cypresses

Cypresses gained ground in Van Gogh’s work by late June 1889 when he resolved to devote one of his first series in Saint-Rémy to the towering trees. Distinctive for their rich impasto, his exuberant on-the-spot studies include the Met’s close-up vertical view of cypresses (49.30) and this majestic horizontal composition, which he illustrated in reed-pen drawings sent to his brother on July 2. Van Gogh regarded the present work as one of his “best” summer landscapes and was prompted that September to make two studio renditions: one on the same scale (National Gallery, London) and the other a smaller replica, intended as a gift for his mother and sister (private collection).

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 822, 2nd floor

Vincent van Gogh: Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler)

Van Gogh produced more than twenty self-portraits during his Parisian sojourn (1886–88). Short of funds but determined nevertheless to hone his skills as a figure painter, he became his own best sitter: “I purposely bought a good enough mirror to work from myself, for want of a model.” This picture, which shows the artist’s awareness of Neo-Impressionist technique and color theory, is one of several that are painted on the reverse of an earlier peasant study.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 825, 2nd floor

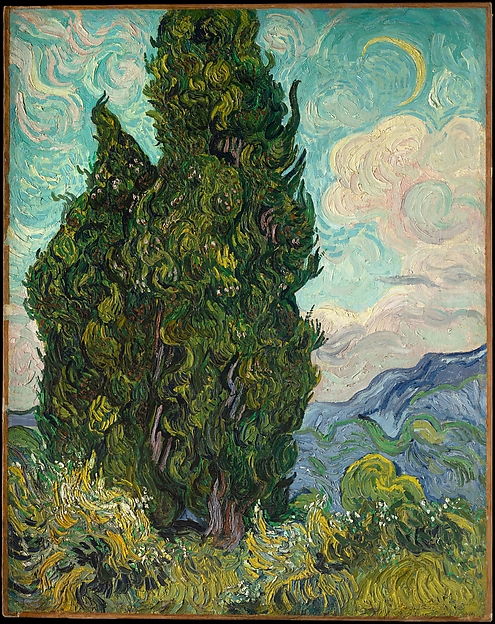

Vincent van Gogh: Cypresses

Cypresses was painted in late June 1889, shortly after Van Gogh began his yearlong stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy. The subject, which he found “beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk,” both captivated and challenged the artist: “It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape, but it’s one of the most interesting dark notes, the most difficult to hit off exactly that I can imagine.” One of two close-up views of the “very tall and massive” trees in a vertical format (the other is in the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), Cypresses was shown in the 1890 Salon des Indépendants.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 825, 2nd floor

Jacques-Louis David: La Mort de Socrate

Accused by the Athenian government of denying the gods and corrupting the young through his teachings, Socrates (469–399 B.C.) was offered the choice of renouncing his beliefs or dying by drinking a cup of hemlock. David shows him prepared to die and discoursing on the immortality of the soul with his grief-stricken disciples.

Painted in 1787 the picture, with its stoic theme, is perhaps David’s most perfect Neoclassical statement. The printmaker and publisher John Boydell wrote to Sir Joshua Reynolds that it was “the greatest effort of art since the Sistine Chapel and the stanze of Raphael.”

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 614, 2nd floor

Pierre Auguste Cot: Springtime

This flirtatious duo in classicizing dress, painted with notable technical finesse, reflects Cot’s allegiance to the academic style of his teachers, including Bouguereau and Cabanel. Exhibited at the Salon of 1873, the picture was Cot’s greatest success, widely admired and copied in engravings, fans, porcelains, and tapestries. Its first owner, hardware tycoon John Wolfe, awarded the work a prime spot in his Manhattan mansion, where visitors delighted in “this reveling pair of children, drunken with first love … this Arcadian idyll, peppered with French spice.” Wolfe’s cousin, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, later commissioned a similar scene from Cot, The Storm, now also in the Metropolitan’s collection (87.15.134).

Pierre Auguste Cot: The Storm

When Cot exhibited this painting at the Salon of 1880, critics speculated about the source of the subject. Some proposed the French novel Paul and Virginie by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737–1814), in which the teenage protagonists run for shelter in a rainstorm, using the heroine’s overskirt as an impromptu umbrella; others suggested the romance Daphnis and Chloe by the ancient Greek writer Longus. New York collector and Metropolitan Museum benefactor Catharine Lorillard Wolfe commissioned the work under the guidance of her cousin John Wolfe, one of Cot’s principal patrons. Like the artist’s earlier Springtime (2012.575), it was immensely popular and extensively reproduced.

Both on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 827, 2nd floor

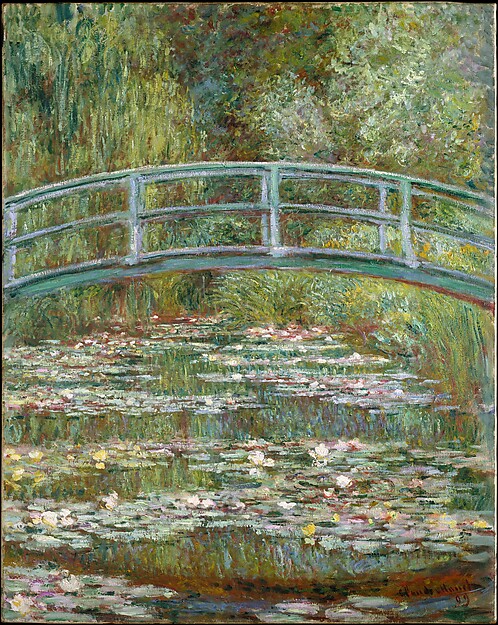

Claude Monet: Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies

In 1893, Monet, a passionate horticulturist, purchased land with a pond near his property in Giverny, intending to build something “for the pleasure of the eye and also for motifs to paint.” The result was his water-lily garden. In 1899, he began a series of eighteen views of the wooden footbridge over the pond, completing twelve paintings, including the present one, that summer. The vertical format of the picture, unusual in this series, gives prominence to the water lilies and their reflections on the pond.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 819, 2nd floor

Paul Cézanne: Still Life with Apples and a Pot of Primroses

Cézanne rarely painted flowering plants or fresh-cut bouquets, which were susceptible to wilting under his protracted gaze. He included potted plants only in three still lifes, two views of the conservatory at the Jas de Bouffan, and about a dozen exquisite watercolors made over the course of two decades (from about 1878 to 1906). Cézanne seems to have reserved this particular table, with its scalloped apron and distinctive bowed legs, for three of his finest still lifes of the 1890s.

This painting was once owned by the ardent gardener Claude Monet.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 825, 2nd floor

Jason Pollock: Pasiphaë

Finished just after Pollock’s first exhibition in 1943 at Peggy Guggenheim’s New York gallery, Art of This Century, Pasiphaë is the largest of the painter’s mythologically themed pictures of the mid-1940s. Originally named Moby Dick, the picture was retitled before it was exhibited in 1944 when James Johnson Sweeney, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, related the story of the Cretan princess Pasiphaë who gave birth to the half-man, half-bull Minotaur. The Minotaur had been a favorite motif of Picasso and of the Surrealists (Minotaure had been the name of their literary magazine from 1933 to 1939, for which Picasso had designed the first cover).

Here Pollock incorporates two sentinel-like standing figures at the left and right and a prostrate figure at center. Pollock weaves these figures into a complex field of arcane symbols and free-form abstraction, his own novel interpretation of the Surrealist practice of automatism, wherein the artist’s unconscious is used to organize composition.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 913, 1st floor

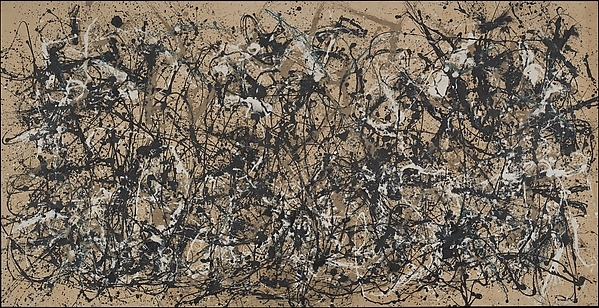

Jason Pollock: Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Biography: (too long…)

In Autumn Rhythm, as in many of his paintings, Pollock first created a complex linear skeleton using black paint. For this initial layer the paint was diluted, so that it soaked into the length of unprimed canvas, thereby inextricably joining image and support. Over this black framework Pollock wove an intricate web of white, brown, and turquoise lines, which produce the contrary visual rhythms and sensations: light and dark, thick and thin, heavy and buoyant, straight and curved, horizontal and vertical. Textural passages that contribute to the painting’s complexity — such as the pooled swirls where two colors meet and the wrinkled skins formed by the build-up of paint — are barely visible in the initial confusion of overlapping lines. Although Pollock’s imagery is nonrepresentational, Autumn Rhythm is evocative of nature, not only in its title but also in its coloring, horizontal orientation, and sense of ground and space.